The recent demise of the United States Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy was—and not without a little irony—barely noticed. Even though the commission reports and Matt Armstrong’s efforts to explain public diplomacy may seem like inside baseball to most US citizens, the loss of the commission is a lost opportunity to help more people better understand how public diplomacy impacts their lives. We need new approaches to engage the general public about the need for a robust public diplomacy that helps us collaborate effectively with peers worldwide to address pressing global challenges.

Now imagine both the short-term and long-term impact on public diplomacy if we set a goal in 2012 to internationalize education for all US students.

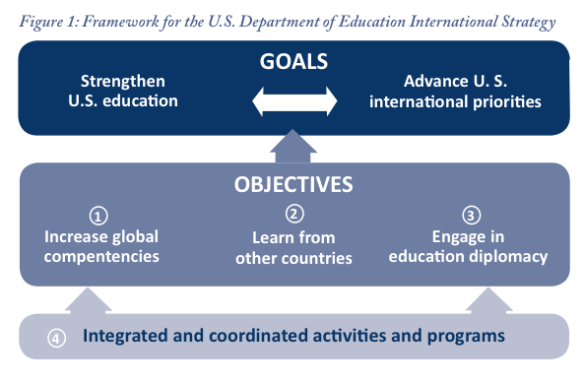

One definition of public diplomacy is that it “seeks to promote the national interest of the United States through understanding, informing and influencing foreign audiences.” Public diplomacy, which is part of “soft power,” “smart power,” and “civilian power,” comes in many flavors, such as “cultural diplomacy” (arts, educational and sports exchanges), and overlaps with and supports “citizen diplomacy.” Successes include Fulbright and International Visitor Leadership exchange programs, Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, and the Peace Corps. New efforts to engage the next generation of young people include multilingual Tweets, tech camps, the @america center in Jakarta, and mobile learning programs. Despite its effectiveness from the Cold War through the Arab Spring, public diplomacy remains a less respected partner of a US foreign affairs approach dominated by development, defense and intelligence. How do we help raise the profile of public diplomacy?

What if we tap the enormous goodwill and peer-to-peer power of 7 million US teachers and their 80 million students? What if we engaged our 130,000 schools to help build a more valued public diplomacy, one that more Americans would more clearly understand, participate in, and respect?

Here is one example of the impact of global classroom connections. Last April, we were honored to host U.S. Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs Judith A. McHale at the Peapod Academy in Redwood City, California with a virtual exchange between Adobe Youth Voices students in California and Pakistan. Diego Petterson, an Adobe Youth Voices educator who leads the journalism program at the Peapod Academy, observed that the virtual exchange had a profound effect on the students in California, who were immediately able to look past accents and appearances to find common ground with their peers in Pakistan:

“Many of the students in our program have come from difficult backgrounds, and they made the association between the ways they have been stereotyped and labeled ‘gangsters’ and the stereotype of being a ‘terrorist’ if you are from Pakistan. The students here expressed a great sense of connection with their peers, wanting more opportunities to connect virtually and to meet them in person, inviting them to the United States,” said Diego.

Efforts like this to debunk stereotypes and facilitate mutual understanding starting at an early age will pay foreign policy dividends for generations.

Connecting US classrooms to partners worldwide provides our students with valuable 21st century skills; it’s also good foreign policy. Teachers and students are an important resource to help us understand and inform foreign audiences. Let’s tap American “classroom power” to lift to prominence US public diplomacy, one our nation’s most important foreign policy efforts to ensure our long-term security and prosperity.

UPDATED: Check out these two recent articles on this topic. The first is from By Robin L. Flanigan Education Week, U.S. Schools Forge Foreign Connections Via Web

“It’s really easy to hate what you don’t know,” said Lisa Nielsen, an international speaker on innovative education and the co-author of Teaching Generation Text, published in 2011 by Jossey-Bass Teacher. “In the future, I think there are going to be big changes in the way countries are defined, because people around the world are going to be connecting and bonding with each other in a way that doesn’t involve places, but their ideas and passions.”

The second is from travel writer Rick Steves, who writes in USA Today:

Americans who want our next generation to be hands-on with the world — grappling constructively with international partners against daunting challenges that ignore political borders, working competitively in a globalized economy, and having enthusiasm rather than anxiety about other cultures and approaches to persistent problems — can get on board with the movement to help our students get a globalized education.

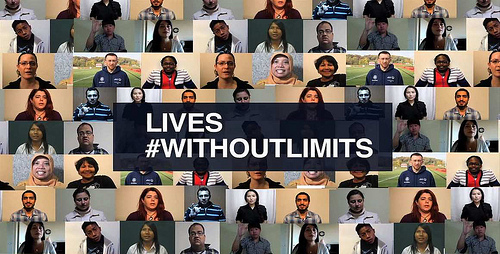

Today, December 3, 2013, in recognition of International Day of Persons with Disabilities, the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA) is launching the “Lives Without Limits” campaign to promote the importance of including persons with disabilities in international exchange programs. The includes stories and features video testimonials from alumni and current students.

Today, December 3, 2013, in recognition of International Day of Persons with Disabilities, the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA) is launching the “Lives Without Limits” campaign to promote the importance of including persons with disabilities in international exchange programs. The includes stories and features video testimonials from alumni and current students.