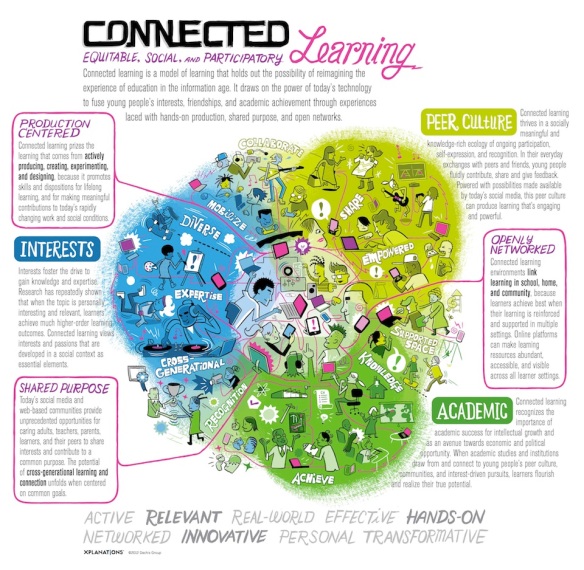

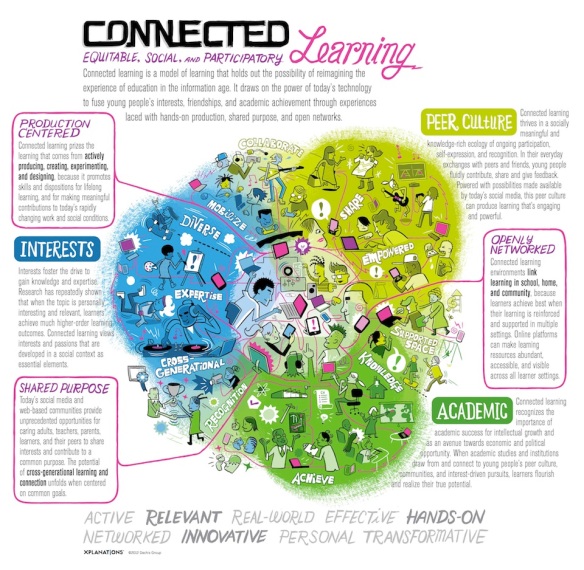

As a kick-off to the badge competition at last week’s DML Conference, UC Irvine Professor Mimi Ito and her team launched the Connected Learning research initiative with a snazzy infographic, a video, and a provocative Ignite talk, where Professor Ito exclaimed that connected learners are “the 1%.” With a nod to Occupy movement, the research network aims to address:

“… this historical moment where we see the rise of social media, the Internet, and a growing disjuncture between formal and informal learning. We suggest a new paradigm for considering the promise of sociality and media and learning, centering on hybrid learning networks which support interest-driven learning, cutting across school, home, after-school, and peer cultures.”

Like many of the thoughtful participants at conference, the MacArthur Foundation-supported Connected Learning team is asking important questions around peer and multi-generational learning, civic engagement and social justice, including:

How effective can the exploding sector of open learning and peer-to-peer learning be?

In what ways can digital media boost learning for marginalized communities?

Can social media and digital technology improve the impact of after-school programs, especially for disadvantaged youth?

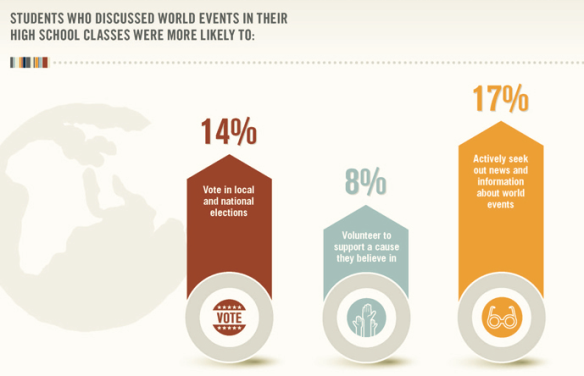

Does learning that is connected to a learner’s interest help produce young people who are more civically engaged and more active 21st-century citizens?

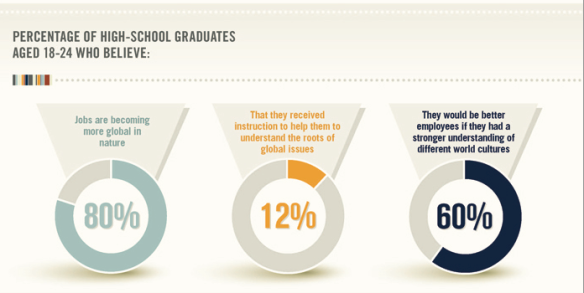

For those of us who have occupied (small “o”) the “connected learning” space for a couple of decades, it is good to see a major foundation fund this research and give classroom civic engagement and social justice issues a higher profile. Conspicuous by its absence, however, is any reference to teachers and students connecting with their peers worldwide. In fact, global classroom collaboration researchers and practitioners in many countries for many years have asked and answered many of these same questions: Does global classroom collaboration boost learning for marginalized communities? Yes. Support peer-to-peer learning? Yes. After-school programs? Disadvantaged youth? Civic Engagement? Yes, yes, and yes.

We hope that the omission of globally connected learning in its launch is not an oversight, and will be an area the team will move into soon. Other teams have found globally connected learning a rich subject to study. Under the guidance of Professor Margaret Riel, for example, graduate students at Pepperdine University, for example, have used Learning Circles each year since 2002 to support and organize action research as part of their online Masters of Arts degree program in Educational Technology. If Professor Ito’s team intends to look at the many superb global classroom programs run by the Connect All Schools partners, it will undoubtedly benefit the research. To launch this research network without any reference to the impact or increasing capabilities of classrooms to connect worldwide seems to miss a key aspect of connected learning.

Furthermore, to launch this research network about connect learning without connecting with research teams in Tunisia, Egypt, Uruguay, Australia, India, Iran, Korea, Russia, Kenya and other countries where social media and digital technology is having a significant impact on teaching and learning, seems a missed opportunity, especially since most mobile learning innovation is happening outside the United States. To study Occupy it makes sense to study it alongside Arab Spring. Why not research the impact of social media and youth civic engagement in collaboration with Tunisian and Egyptian education researchers? Or why not work with Korean researchers to examine if games can used to address social issues? When it comes to connected learning, it makes sense to research with the world, not just about it.

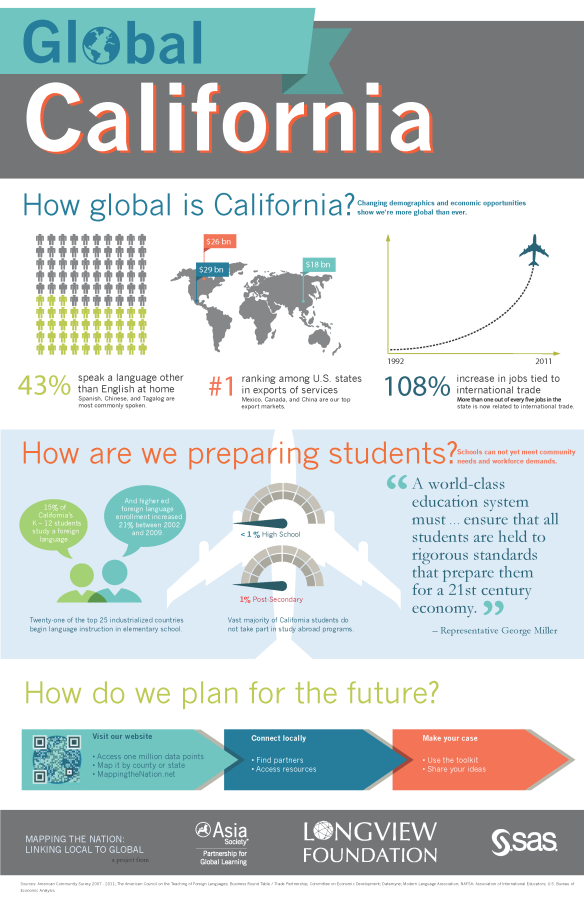

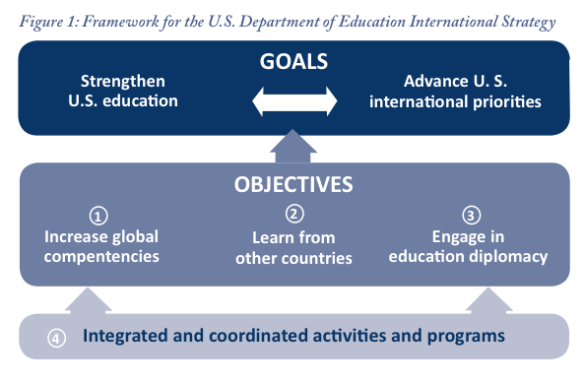

The goal of Connect All Schools is to give every US school the opportunity to connect with an international partner by 2016. We’ve made the case that globally connected learning is both a national security issue and good foreign policy strategy. Connecting classrooms globally is also an issue of social justice. We invite the Connected Learning team to learn more about how relevant, engaging, and empowering globally connected learning is for children around the world.

Is the U.S. ready for a global future?

Is the U.S. ready for a global future?