Clint Eastwood’s “Halftime in America” Super Bowl commercial was focused on Detroit and the auto industry, but it could just as well have been describing our country’s international exchange programs. In a new globally connected, mobile, social, “anytime, anywhere” DIY world of cross-border connections, does the exchange field have a team ready to play the second half?

A young Dwight D. Eisenhower (front row, second from right) during backyard football practice, Abilene, Kansas. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

The first half began in earnest on September 11, 1956, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower launched the People-to-People Program to:

… enhance international understanding and friendship through educational, cultural and humanitarian activities involving the exchange of ideas and experiences directly among peoples of different countries and diverse cultures. President Eisenhower felt that creating understanding between people was essential to building the road to enduring peace and envisioned programs such as city affiliations, pen-pals, stamp exchanges, international sporting events, musical concerts, hospitality programs, theatrical tours and book drives as the means to achieving that goal – a critical goal in the existing Cold War climate.

Complemented by US government-sponsored programs such as Fulbright and Peace Corps, the “citizen diplomacy” that President Eisenhower championed increased cross-cultural understanding and bolstered America’s image abroad through the end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the United States Information Agency, which had nurtured the people-to-people movement since its inception. The end of the first half for international exchange was not a result of a changing world or national politics, however. It was technological, as teacher-librarian Anne Lambert

recounts:

I grew up fifteen minutes from the US-Mexico border in the ‘60’s, and I was always interested in people and cultures. As a teacher I arranged day trips to Tijuana, Mexico, worldwide pen pals, and student exchange programs in Ensenada, Mazatlan, and Europe. By the 90’s I saw the Internet as an opportunity for students to travel virtually and to learn languages…

I found iEARN to be welcoming and empowering, reaching across distance, language, ethnicity, wealth, and academic achievement. Student by student, the worldwide classroom of each iEARN project broke down stereotypes and invited our whole community to experience the power of communication.

Lumaphone link between Walworth School, London and Foster High School, Wa. USA, 1990

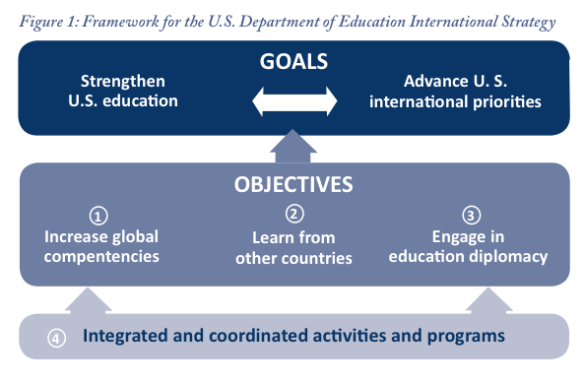

What Anne describes is what we now call “Exchange 2.0,” which is defined as “the use of new media and communications technologies to expand, extend, and deepen international cross-cultural exchanges.” Exchange 2.0 is not a new idea, as iEARN’s Ed Gragert outlined in his white paper for the US Department of Education in 2000 as a precursor to the inaugural International Education Week:

Through the Internet, significant opportunity exists for human-to-human interactions, experiential learning and direct curriculum applications. Our students have the opportunity to both learn and teach through direct interaction. Further, students have the opportunity to observe, learn and address the serious global issues for which education is designed to prepare them as adults. Technology now gives students the means to directly interact on these issues. …

During the past 15 years, there has been a general progression in on-line international education, characterized by the following over-simplified steps:

1) In the late 1980s, foreign language teachers (and ESL teachers in other countries) were some of the first to recognize the potential for this technology to bring authentic interaction and materials into their classrooms.

2) In the 1990s, global studies and world affairs teachers learned that they could heighten interest in the issues being discussed if their classes were interacting with real students and teachers in the countries that were in the news or were part of the curriculum.

3) In 2000, international collaborative education is on the threshold of being integrated into all aspects of a teacher’s curriculum and we are fortunate to have educators who now have 5-10 years of experience to help with professional development

Twelve years later, international collaborative education has not been integrated into most teachers’ curricula, but the recent explosive growth of social media and mobile phones worldwide has created opportunities for students and teachers to connect at a scale unimaginable just a few years ago. The entire concept of “exchange” is being redefined, and as Tech Change’s TJ Thomander notes, virtual exchange will play more than simply a supporting role for traditional exchange:

Digital intercultural conversation is meant to be a complement, not a replacement to face-to-face interaction. But for most of the world that doesn’t have the means to travel, this will be the only option that they have. It won’t be a complement [or] a replacement; it will just be the only way that they develop relationships with others across borders.

It’s “game on” for virtual exchange; is it “game over” for traditional travel-based exchange programs?

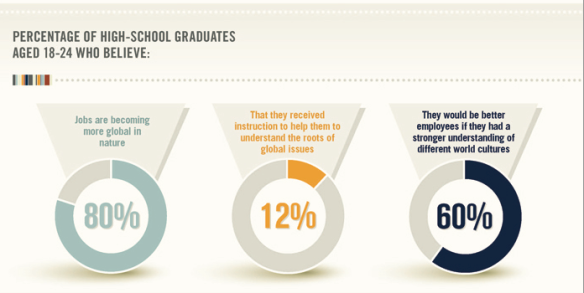

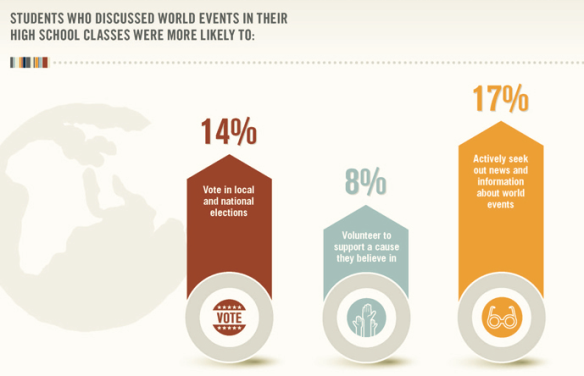

The power of physical exchanges is undeniable. Yet, in 2010, only 1,979 US high school students traveled abroad for a semester or yearlong exchange experience, at an estimated cost of $15,000 to $20,000 each. At a fraction of the cost classroom-powered diplomacy already dwarfs all travel programs combined, while allowing the very young, boys, those with learning challenges and physical disabilities, and others not able or inclined to travel to engage with peers abroad. For the vast majority of students around the globe, short codes are more likely to offer future employment and English language learning opportunities than a one-in-a-thousand chance to be selected for an exchange program. Furthermore, virtual exchange is an option that empowers participants to facilitate, monitor, and assess their own cross-cultural interaction. Teachers need not apply for a J-1 visa to coordinate Skype calls between kindergarten classrooms or create their own Twitter hashtags to collaborate with their peers worldwide.

The knowledge and experience gained from the first fifty-five years of citizen diplomacy and international exchange is not irrelevant, however, in this new era of global connectivity. Quite the opposite: Face to face still trumps Facebook to Facebook, and a J-1 visa for the YES program is much more likely to transform a young person’s life than a hashtag. Just like the US education system is experimenting with “blended” models of classroom-based and online teaching and learning, the Connect All Schools consortium is experimenting with blended models of virtual and travel-based exchange programs. Partners such as American Councils, AFS-USA, Mobility International, IREX, Teachers without Borders, TakingITGlobal, Plan International and Youth Service America are helping to create an entirely new field of social entrepreneurship and community service-infused programs, including professional development for supporting teachers to integrate international exchange into their curricula.

It’s important work, and a talented, passionate team of tech-savvy international exchange professionals is ready to take the field.

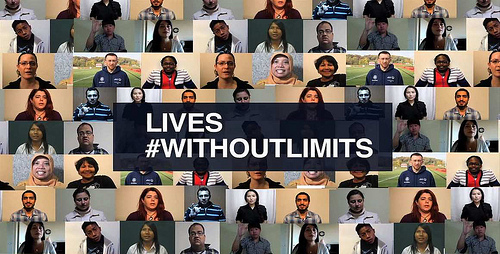

Today, December 3, 2013, in recognition of International Day of Persons with Disabilities, the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA) is launching the “Lives Without Limits” campaign to promote the importance of including persons with disabilities in international exchange programs. The includes stories and features video testimonials from alumni and current students.

Today, December 3, 2013, in recognition of International Day of Persons with Disabilities, the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA) is launching the “Lives Without Limits” campaign to promote the importance of including persons with disabilities in international exchange programs. The includes stories and features video testimonials from alumni and current students.